One of the many stories or legends still told of early Brookhaven/South Haven is that of the famous Senator Daniel Webster, and of the monstrous trout caught in the pond below the Samuel Carman’s mills on the Connecticut or Carmen’s river.

The New York Gazette of 29 June 1821, is said to have reported: “A very large salmon-trout, weighing thirteen pounds eight ounces, and three feet in length, and seventeen inches round, was caught by Mr. Samuel Carman, Jr., in his pond at Fire-Place, Long Island, on the 24th inst.” The New York Evening Post is said to have confirmed the story “by three of our most respectable citizens.”

The above accounts likely report the origin event that led to the “Webster” trout legend which became much embellished with time. It is interesting to note that Daniel Webster was not mentioned in these origin accounts.

Others, however, date the Webster trout event variously dates in the 1820s. Sources for these dates have not yet been found.

There are several artifacts still extant almost two centuries after the event which assist in telling the story. One is a wooden carved weathervane said to have been based on an original drawing made at the time of the catch, and which, for a time, rested atop the South Haven Presbyterian Church steeple; another is a Currier and Ives lithograph thought by some (generally in fishing circles) to depict Daniel Webster catching the trout in the river; and the third is a plaque on a pew in the nearby old South Haven Presbyterian Church identifying the Suffolk Club, a well know hunting and fishing club which occupied the banks of the river and to which Daniel Webster is said to have been associated, at least in its early 19th century iteration.

There is little question that Daniel Webster and Samuel Carman were friends, and that Webster, along with other wealthy and influential New Yorkers, regularly visited the Carman tavern and inn to fish in the adjacent river. However, there is little contemporaneous evidence that Webster himself caught the record-sized trout, or that the event took place in the context of a Sunday morning church service, as some recount below.

“Fish stories” are not always told by fishermen.

Pictured below is said to be the trout that, in the 1895 Brooklyn Eagle article below, was “sawed out of an inch board, and this Mr. Carman had rigged up as a weather vane for his barn, and it is still doing duty to show the way the wind blows at the Carman homestead.”

It, or another facsimile, early on became the weathervane atop the steeple of the South Haven Presbyterian Church across the road from the Carman homestead/inn. It was said to have been struck by lightning and fell to the ground. The original of this fish weathervane is now on loan by the church to the Bellport-Brookhaven Historical Society museum. In 1976, two replicas of this fish were made, one of which was placed atop the Presbyterian church steeple, the other atop a flag-pole at the historical society.

The fish was reluctant to maintain its perch, however, and was twice dislodged after 1976—the most recent in a violent nor’easter on March 13, 2010, with recorded winds of 60-75+ mph, which caused considerable damage across Long Island.

Some have suggested that the so-called “Daniel Webster” trout caught in the Carman’s River was probably what is known as a “salmon-trout” which, it is said, can grow to enormous size, and spends part of its life cycle in salt water. See Richard A. Thomas references, this page.

Old South Haven

Church Steeple, 1990

In addition to the above mention in the New York Gazette and New York York Evening Post, the giant fish is mentioned in the Niles Weekly Register of the same period—specifically attributing its capture to Samuel Carmen, Jr.

Niles’ Weekly Register, edited by Hezekiah Niles, Vol. 20, from March to September 1821, p. 304*

Trout, a very large one

Mammoth trout. At “Fireplace,” Long Island, about 70 miles from New-York, Mr. Samuel Carman, jun. on the 25th ult. caught at the “tail of his saw mill” a trout three feet in length and 17 inches round the girth, and weighing 13 lbs. 8 oz. It was kept alive in a pen several days for the gratification of the curious, the largest trout ever caught before, in the remembrance of the oldest inhabitants, never having exceeded 5 lbs. in weight—seldom being more than 2½ lbs.

*Niles’ Weekly Register containing Political, Historical, Geographical, Scientifical, Statistical, Economical, and Biographical Documents, Essays, and Facts; Together with Notices of the Arts and Manufactures, and a Record of the Events of the Times; H. Niles, Editor.

The following article from the Brooklyn Eagle is the first account of the trout legend so far found that connects Daniel Webster with a huge trout caught in the Carman’s River. While modern telling of the story has Daniel Webster catching the fish, we have not found any 19th century accounts where Webster is the actual fisherman. In this account he just purchases the trout at extraordinary cost after it has been captured by others. If one were to read just the headlines, one can see how the legend was beginning to develop.

It is also interesting to note that in this account no mention is made of the South Haven Presbyterian Church, or that the drama of the fish’s capture has anything to do with the church.

Many local skeptics believe that the fish was caught by some anonymous local, or perhaps Samuel Carman himself, and embellished, as fishermen are wont to do, over the decades.

The major focus of this this article is the dispute between landowners—in this case the famous Suffolk Club and the Tangier Smith family—over who actually owned the Carman’s River. This was a dispute that continued into the 20th century.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle—Sunday, 15 December. 1895

DANIEL WEBSTER’S BIG TROUT.

It Weighed Fourteen Pounds and was Caught on Long Island.

HIS TRIPS TO CARMAN’S RIVER.

Autograph Letters of the Great Jurist Produced in a Law Suit at Riverhead, Showing That He Did What He Could for His Old Friend, Samuel Carman, in a Dispute With the Long Island Railroad

An interesting ejectment suit involving the title to important fishing grounds at Carman’s river, South Haven, was decided at the last session of the Suffolk county court, at Riverhead. The plaintiffs in the suit were William E. T. Smith and others and the Suffolk club was the defendant. The plaintiffs claimed title to the territory stretching north from the south country road along the river. They are the sons and daughters of the late Egbert Tangier Smith and claim title to the property in question by virtue of deeds and wills dating back to the seventeenth century, their claim resting mainly on an old colonial patent. The Suffolk club, the defendant, which was organized in 1865, is composed of men so wealthy that a candidate for membership must be worth at least $500,000![]() before he can be as much as proposed. The club claimed to own ninety acres of land there and to hold many more acres leased property, together with the fishing and hunting privileges of Henry Carman. They traced their claim to Samuel Carman, Henry’s father, who owned all the land and their streams and fishing privileges by deeds from the first settlers. To substantiate this claim ex-Judge Reid and August Haviland, who appeared for the club, submitted two autograph letters of Daniel Webster, to show that in an old action in which Carman was once involved with the Long Island, Webster, who was an old friend of Carman, had examined the deeds and found that he was the identical owner of the property, streams and fishing privileges involved in the suit then being tried. In spite of the autograph testimony of the great jurist the jury found for the plaintiff in the sum of $250 damages.

before he can be as much as proposed. The club claimed to own ninety acres of land there and to hold many more acres leased property, together with the fishing and hunting privileges of Henry Carman. They traced their claim to Samuel Carman, Henry’s father, who owned all the land and their streams and fishing privileges by deeds from the first settlers. To substantiate this claim ex-Judge Reid and August Haviland, who appeared for the club, submitted two autograph letters of Daniel Webster, to show that in an old action in which Carman was once involved with the Long Island, Webster, who was an old friend of Carman, had examined the deeds and found that he was the identical owner of the property, streams and fishing privileges involved in the suit then being tried. In spite of the autograph testimony of the great jurist the jury found for the plaintiff in the sum of $250 damages.

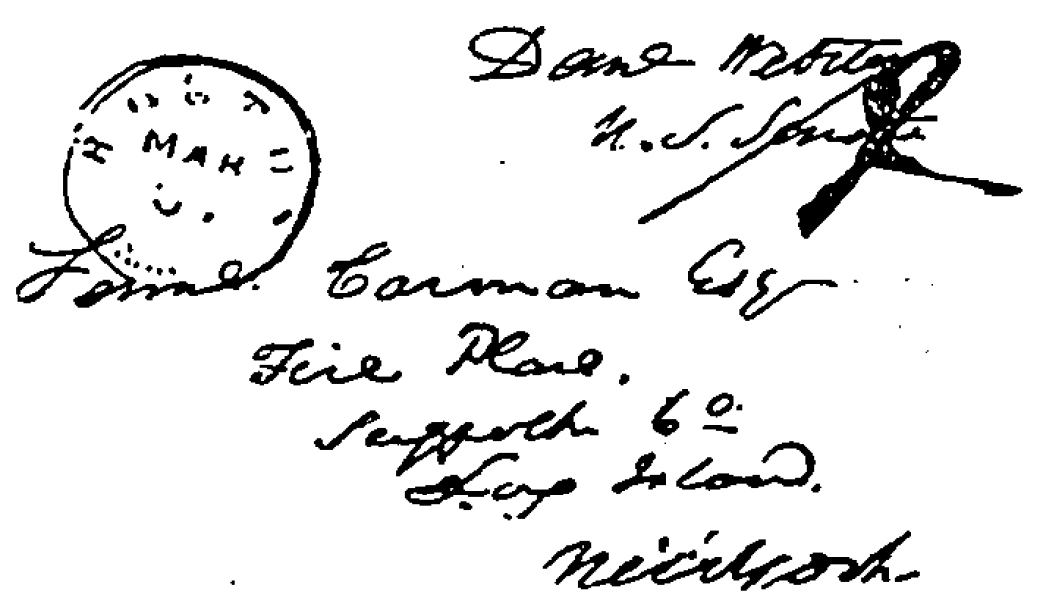

Mr. Haviland, who is the custodian of the Webster letters, intrusted (sic) an Eagle representative with the shorter epistle to Samuel Carman, in order that it be reproduced in fac simile, and here it is.

That Webster made use of his franking privilege to forward the letter, as was the custom with United States senators and representatives at that time, is clear from the envelope, of which this is a reproduction:

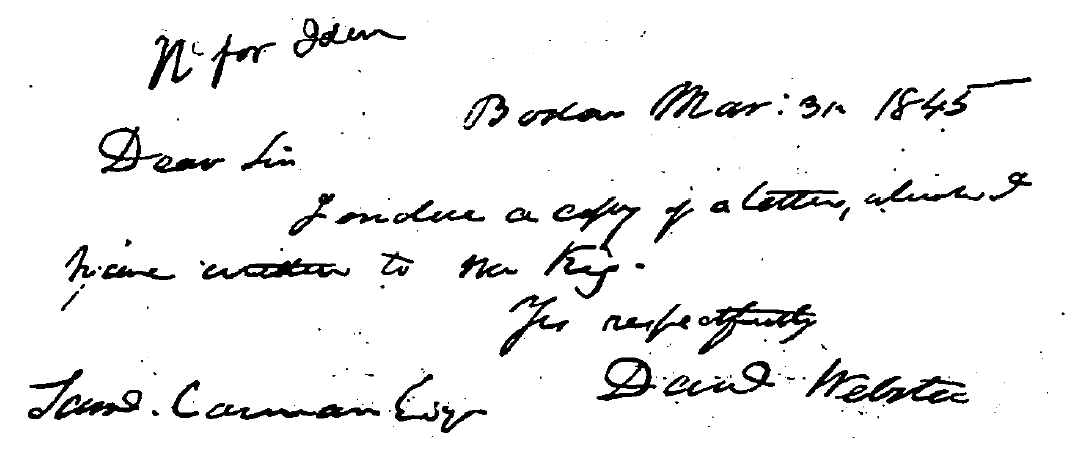

The copy of the letter to Mr. King, which Webster inclosed (sic) to his friend Carman, is as follows:

Boston, March 31, 1845.

My dear sir—I was at Fire Place last week and Mr. Carman consulted me professionally on the subject of the of the Long Island railroad in making a dam over the river, etc. He placed his deeds in my hands that I might see what his title really and actually is.

I find that he is owner of all the land on the west side of the river from his house northerly to the north line of the George’s or Smith’s manor and I find also by express grant in all the deeds he is sole owner of the whole stream. His eastern boundary thereof is the easternj edge of the stream or its banks from the crossing place below his mill to the northern line of the patent which is half or three-quarters of a mile north of the railroad.

In damming up this stream it is clear that the company are mere tresspassers (sic) and he has a right clearly to abate the nuisance by taking away the dam if he pleases. But he is well disposed and reasonable and I am sure that the company will not be less so.

The dam is injurious to him in several ways. First it renders the supply of water to his own mill below less regular. Secondly, it completely cuts off the passage up and down of the fish and must destroy the whole race, by depriving them of their spawning grounds. This is no small matter, considering the value and use of his establishments, but finally, the site would make a mill power for his own use equal, as he thinks, to the one below.

It strikes me the cause is one for compromise and adjustment.

You are interested in the company and know all the gentlemen and I am very sincere friend to the road and shall advise Mr. Carman to be reasonable and equitable and have no doubt he will be so. The matter of the passage for fish can be well enough provided for by suitable stairs or path to let them up and down and the rest is the proper subject for just estimate.

I told Mr. Carman that I would write you when I had considered the subject, as he looks on you as friendly to him, and at the same time that you have an interest in the road.

Probably I may see you in New York in the course of next week.

DANL. WEBSTER

Hon. Jno. King.

Fire Place, to which Webster refers in his letter, is now known as South Haven and sometimes by the old name of Carman’s river. It lies on the west side of the river, about two miles from its mouth, and has now, as it had in 1845, an inviting, quiet, homelike air about it. It was at a spot near there that the Suffolk club built its handsome club house, and having secured the privilege of fishing in the stream from Uncle Sam Carman as he was familiarly known. It was a celebrated fishing spot and lovers of of the sport from all parts of the country came there to fish. His guest included the fine men of the country in those days. Uncle Sam is described as a most sociable boniface, and he was Uncle Sam to everybody. His wife was a jolly woman, too, and any visitor was made to feel at right at home at the Carman homestead.

Uncle Sam and Webster were great friends, and Webster came there to fish for twenty years or more. The company always had plenty of brandy, and together with lots of tobacco, the evenings were spent around the old fashioned fireplace of Uncle Sam’s house in a jolly, sociable manner. The old Carman homestead still stands in a well preserved condition. It is occupied by Henry W. Carman, Sam’s son, and Nathaniel Miller’s wife, of Brookhaven is a daughter of Uncle Sam Carman. Uncle Sam was a miller, which, in those days, made him very popular, for people came to his mill from miles around. It was a grist mill and he did a thriving business. His sons now run the mill, which has been in operation for more than 120 years.

An interesting incident in the life of Uncle Sam is told by an old personal friend of his. Uncle Sam was a great lover of the pipe and smoked almost incessantly. Mart Raynor from the manor was also a great smoker, and the question arose who could smoke the most. A wager was made to decide it, and they they were to smoke and eat nothing save bunkers, a quantity of which were prepared for the occasion. After smoking constantly for two days and nights they gave it up and called it a draw.

The largest trout ever caught on Long Island was caught in Carman’s river. It weighed fourteen pounds, and when news of the wonderful catch reached Daniel Webster he went down with a party of friends and paid $100 for the trout, which was served at a big dinner given to Webster’s friends in New York city. Some of those who accompanied Webster on this fishing trip to Uncle Sam Carman’s were Attorney General Hoffman, Philo T. Ruggles, the celebrated lawyer; Chief Justice Thomas J. Oakley, Judge William S. Rockwell, George P. Barker, David Graham, Henry A. Cram, James A Gerard and John J. Crittenden, senator from Kentucky.

Before Mr. Carman parted with the big trout a fac simile of it was sawed out of an inch board, and this Mr. Carman had rigged up as a weather vane for his barn, and it is still doing duty to show the way the wind blows at the Carman homestead.

The occasion of Webster’s letter arose out of a dispute between Carman and the Long Island Railroad company as to whether the latter had a right to construct an embankment that would back up the water the celebrated trout stream. Uncle Sam wrote to his friend Webster asking for legal advice upon the subject, and the result was that Webster took up the cause of his ole friend and wrote the letter quoted above to John A. King, then acting as the representative of the road, in the matter.

Mr. Carman later received another letter from Webster which is also a cherished heirloom. It seems that Webster, during his twenty annual visits to Uncle Sam’s had never paid him a cent for his accommodation. After the matter was satisfactorily settled with the road Webster wrote Carman saying: “I would charge anyone else fifty dollars ($50) for this advice. So you can credit me with fifty dollars on our account.”

By the 1930s, this Webster legend had grown such that, as the story now goes, Daniel Webster was attending the church service at the Presbyterian church nearby when a slave/servant came in and loudly whispered to Webster that the giant fish was seen in the pond. Webster quickly got up and left. The remaining congregation also soon went outside and lined the pond’s bank, causing the minister to terminate his sermon and join them. Webster then makes a dramatic catch, has the wood carving made, and takes the fish to New York where a feast is prepared hosted by Webster at Delmonico’s.

This version, as detailed by the Rev. George Borthwick (known for his story telling) in his book The Church at the South, A History of the South Haven Church, now takes three pages to tell.

The Church at the South: A History of the South Haven Church. Rev. George Borthwick.

Original manuscript c. 1939; published 1989. p. 186ff.

Daniel Webster’s Big Trout

The [Carmans] river which furnished power for [Samuel Carman’s] mills was noted for the trout it contained, and he capitalized on that. So great was the reputation of this stream among fishermen that a historian of that day states the common opinion that its trout fishery was “superior to any other in this part of the country.” Hither came groups of fishermen by stage-coach from New York City, staying during their visit in South Haven at the tavern. Of one such group, composed of Sen. Daniel Webster, Phillip Hone, Walter Bowne, Martin Van Buren, and John and Edward Stevens, is told a story the historicity of which is beyond question.

The details of this story, as they have come down through the years since that day in 1827 when it took place, have been colored by the countless tellings of one person to another. The common tradition states that Daniel Webster had tried unsuccessfully for some time to hook a huge trout which he knew was in the river. One Sunday morning, after instructing one of Sam Carman’s Negroes to watch the stream by the mill to see if he could get a glimpse of the monster, he went to the church across the way with his host. “Priest” King’s long sermon had not reached “ninthly” before the Negro had crept into the church up to the front pew in which sat Sam Carman and Senator Webster. In a whisper which excitement made so loud that it was heard by all the worshippers near the pew, he informed Mr. Webster that the fish was lazily swimming in a pool below the mill. Daniel Webster tiptoed out, and then Samuel Carman, and then boys who managed to elude the watchful eyes of their parents. Finally, curiosity overcame so many of the people that Mr. King, realizing his sermon was reaching the ears of a constantly diminishing congregation, concluded it, gave the benediction, and went over to the mill with the remainder of his flock to watch Daniel Webster catch what proved to be the second largest trout on record. It was some time before the delighted fisherman got a bite from the fish. Suddenly the Senator felt his line tighten and saw thrashing on the end of it the trout which he had long hoped to catch. It was an opportunity of which fishermen dream, but which rarely comes to them. With the excited advice of the worshippers of the South Haven Church, he played the huge fish skillfully until finally he had landed it with his net. There on the ground lay a trout, which when weighed, tipped the scales at 14.5 pounds – a quarter of a pound lighter than the present world’s record, according to the magazine FIELD AND STREAM, which carried this story. Such an event was too important to allow to pass unrecorded. As there were no cameras in that day, the fish was put up against the wall of Sam Carman’s house, and its outline was drawn there. Phillip Hone, copying it, had a weathervane cut out of cherry, one third larger than the trout, so that it would appear the natural size when seen from the ground. He gilded it, and had it placed on top of the South Haven Church spire. There for about half a century it pointed the direction of the wind and reminded the parishioners of their distinguished visitor who had performed so notably in a field in which history does not remember him. One summer’s afternoon, during a thunder-storm, a bolt of lightning struck that steeple, knocked off the wooden fish, and killed a mule that had taken shelter against the side of the church below. The fish can still be seen, weather-beaten and nicked by the storms that have blown about it, in the possession of a church member, Mr. George Miller, the great grandson of Samuel Carman, who had played host to the distinguished fisherman.

Daniel Webster, celebrating this feat with his friends that night before a blazing fire in the tavern, drank too much of Carman’s rum. Tradition states that he became so intoxicated that he could not find his way to his room upstairs, and had to be carried up by his host. The fish he caught was taken to New York City, and there at famous Delmonico’s, cooked and served at a banquet which the Senator gave for his friends. So pleased was he with his good luck, he sent Sam Carman a purse of $100 and came back again many times with his friends Phillip Hone, Walter Bowne, Martin Van Buren, and John and Edward Stevens. They later rented land on the river, hired fishing privileges from Mr. Carman, and formed the nucleus of a group which years after became known as “The Suffolk Club,” widely recognized as the wealthiest club of its size in the world. One of its famous members was Theodore Roosevelt. This organization must have been composed, at least in part, of regular church-goers, for they reserved for themselves a pew in the center of the church, with the words “Suffolk Club” engraved on it.

In addition to the references displayed on this page, Dr. Thomas, in this bibliography, lists other references to trout (including their textual content), especially “big” trout, as they may relate to Webster’s “trout.”

Catching a Trout, We Hab You Now, Sar!—While the subject of this N. Currier lithographFootnote is widely reported, both locally and elsewhere, as being of Daniel Webster and his slave (or servant) at the Carman’s River in South Haven, L.I., NY, the preponderance of evidence is that it has nothing to do with either Daniel Webster nor the catching of a giant trout in the Carman’s River.. It was done by Otto Knirsch ca. 1854-7 after a painting by Arthur Fitzwilliam TaitFootnote some 35 years after the reputed Daniel Webster incident.

See Dr. Richard A. Thomas: Notes on “Catching a Trout.”

When the association between the print and Daniel Webster came about hasn’t been established; except it was well known that Daniel Webster was a trout fisherman and a friend of Samuel Carman, proprietor of the mill and pond, and the inn on its shore. Perhaps some thought the person in the print bore a resemblance to Daniel Webster. 1854 is long after the event—Daniel Webster and the Big Trout—supposedly occurred, and the association of that event with this N. Currier print seems to be of fairly recent origin. Rev. George Borthwick, in his telling of the story (pp. 186-189 in The Church at the South, A History of the South Haven Church, completed in 1939 but not published until 1982) makes no mention of the lithograph. Other evidence appears to demolish the claim that the print shows Daniel Webster catching a fish in the pool below Samuel Carman’s mills at Fire Place (or anywhere else, for that matter).

An original of this lithograph is on loan to the Bellport-Brookhaven Historical Society museum by the Old South Haven Presbyterian church.

The following article, from a 1906 issue of Forest and Stream (predecessor to Field and Stream) provides a somewhat more fanciful account of the great trout. In this account, Daniel Webster is not present at its capture. However the drama of the event now involves a Sunday service at the Presbyterian church.

In the account, the fish is caged in, but allowed to live for a time. Daniel Webster is notified of the trout’s capture, orders that it be kept alive until he can travel out to the Island. He purchases it for a reasonable amount, and returns with it to New York City where it is served at a private dinner party.

Forest and Stream, Saturday, June 23, 1906, p. 999

The Webster Trout

The thriving little city of Patchogue out on Long Island is the center of a trout district that before the day of private preserves could not be beaten either for big fish or ease in getting at them. Even now sport can be had there if one knows where to go. Almost every male in the town is a trout fisherman, but the chief by common consent is Judge A. H. CarmanAstor House Footnote, president of the Carman River Fishing Club. The Judge can tell a good story well, as witness the following:

“This region was the favorite fishing ground of Daniel Webster. He would begin at the bay and fish our streams back to their source in the middle of the island, ten or twelve miles. Henry Clay sometimes fished with him. There was a big trout in Carman’s River they could never get to take the hook; neither could any one else, though scores had seen him. and according to the stories told he was as big as a small whale.

“One hot June day, when all the townspeople were at church and the minister had just got to his sixthly, Carman’s little nigger boy rushed in, mouth open, eyes bulging, one hand holding up his baggy trousers, and yelling, ‘The big trout is in the hole! The big trout is in the hole!’ All knew what hole was meant. It was a spring under a big willow tree, where Carman’s dairy house had once stood, and sent a little brook into the river. So every man and boy in the house was on his feet in an instant.

“‘Hold on, brethren,’ shouted the parson, who was a fisherman himself, ‘let’s all have a fair start.’ Then they made a rush across the fields for the old spring hole, the women and girls tagging after. Arrived there, their first thought was to stop up the entrance, then they got out Carman’s old menhaden seine that hadn’t seen the water in ten years and was full of holes, and wrapped it round and round the sides and bottom of the hole, while the big trout made the water boil as an accompaniment.

“At last, having him hard and fast, they went back and completed their devotions. Next day some one sent a telegram to Webster, and he sent back a check of ten dollars for the trout, and ordered him held alive until he arrived. He came as soon as the stage coach could bring him, and in his presence the trout was taken out, laid on a broad oak plank and his outline carefully drawn with chalk. From this a weather vane was cut out and swung on Sam Carman’s mill for years, or until a West India cyclone came up the coast and split it so it fell. It is still in existence, however, and you will find it in the shop of Nathaniel Miller, one of. our oldest residents.

“Webster took the trout to New York, invited in all his friends and made a grand banquet of it in the Astor House Astor House Footnote, where he always stopped when in the city. The feast was held in the northeast room, second floor, the Vesey street and Broadway corner.

“There is a boy at Artist Lake, where I some times go fishing for black bass,” continued the Judge, “who will be a millionaire if he lives. It is a pretty little sheet of water several miles cast of Ronkonkoma, and I usually have better luck there than at the larger and better known lake. One day when I was going up I wrote to this boy in advance and told him to have all the small frogs he could get at the lake on a certain day. He demanded two cents apiece, which I agreed to pay. Well, we got there, and there was my boy with a dry-goods box full of frogs, and a cheese cloth over them to keep them from hopping out. He had enlisted all the small boys and scoured the country for miles around. It cost me five dollars to settle the bill.” C. B. T.

This article from Early American Life provides a modern, even more fanciful telling of the events.

Early American Life, Volume 6 By Early American Society, April 1975, p. 4ff. Historical Times, Inc, Cowles Magazines, Inc.

This Month’s Weathervane

We are indebted to Jamie Pokorny, who recently spent a month as part of our EAS editorial staff on a brief internship in connection with her college studies, for the following story, which she wrote to describe her favorite weathervane: The South Haven, New York, weathervane is a 150-year-old replica of a trout, carved in cherry wood and measuring four feet by one foot.

Until very recently, Long Island was a sportsman’s paradise. Farming was the principal source of livelihood, wildlife flourished in woodlands and meadows, and natives boasted that Long Island streams offered some of the best trout fishing in the Northeast.

One fishing enthusiast was Daniel Webster, American lawyer and statesman of the early 19th century. Along with friends Martin Van Buren, Philip Hone (New York businessman and mayor of the city in 1825), and John and Edward Stevens (New York inventors and engineers of steamboat and rail transportation fame), Webster often stayed in the village of South Haven at the tavern owned and operated by Samuel Carmen.

Carmen play an influential role in the village of South Haven. Besides the tavern, he owned a general store and several mills located on a river that today bears his name. Like most general stores of the early 1800’s, Sam Carmen’s stocked everything from thimbles and shoes to snuff and rum! His shop also doubled as post office and bank. Carmen’s grist mills ground the local wheat and corn, and his sawmills cut into timber the pine and oak logs felled in nearby forests.

Since there were no public buildings in South Haven, Carmen’s tavern gained prestige as a political center. Meetings and elections were held there, and because the weekly stagecoach from Brooklyn to Sag Harbor made a scheduled stop at the tavern, it became a center for the dissemination of news.

On a Sunday morning in 1823, Daniel Webster was attending morning service at the South Haven Presbyterian Church located very near to Carmen’s River. Webster had been trying vainly for several days to hook a giant trout said to inhabit the river. The sermon had hardly begun when one of Carmen’s employees, who had been posted to watch for the fish, tiptoed into the church and whispered in Webster’s ear. Webster followed the man out and headed for a small pool in the stream. Sam Carmen, unable to contain his curiosity, soon left the church, followed by several small boys. More and more of the congregation drifted out, for the “big fish” was a local legend. The Reverend “Priest” King eventually cut short his sermon, gave the benediction, and himself sped to the mill pond!

Daniel Webster was successful, and hooked a 14½-pound trout that, until 1935, was the second largest trout ever caught in America. A record of the fish was made by a tracing of its outline on the wall of Carmen’s house. Webster, while celebrating his success, is said to have drunk too much of Carmen’s rum and was carried upstairs by the proprietor. It is a fact that Webster later sent Carmen one hundred dollars and returned often to fish.

The trout was taken to the famous Delmonico’s restaurant in New York City and provided the main course for a banquet given by Webster for his friends.

To apologize for disrupting Sunday service, and to leave a reminder of Webster’s feat, Philip Hone ordered a weathervane carved in the exact likeness of the trout, but one-third larger. It was gilded and erected on the steeple of the South Haven church.

A few years later, Webster and his friends formed a fishing group. Among its members through the years have been many wealthy and influential men, including Theodore RooseveltFootnote. They rented land and fishing privileges from Sam Carmen and became known The Suffolk Club, “widely recognized as the wealthiest club of its size in the world .” A pew with a metal plate inscribed “Suffolk Club” remains in the church today.

In 1873 the church steeple was struck by lightning and the vane came down. It was replaced by a more permanent vane. Webster’s trout is now located in the pastor’s home.

In 1960 the South Haven Church was moved a few miles to the small hamlet of Brookhaven. The structure, though, hasn’t changed much since the early 1800’s and the story of Daniel Webster and his trout is still a popular one in the area.

The content or format of this subpage last updated: 09/28/2012 15:07:48

And this version adds even more details to the “fish tale.”

Trout, Volume 1

Ernest George Schwiebert

E.P. Dutton, 1984 – 1834 pages

American Species of Trout and Grayling “The Aphrodite of the Hemlocks”

p. 245

Many early figures like Cotton Mather, Joseph Secombe, Daniel Webster, and Henry Ward Beecher were often found on [Long Island] trout water. Brook trout from the slow-flowing Nissequogue and weedy little Carman’s River on Long Island were favorites of Daniel Webster, and the region still abounds in anecdotes about his brook-trout fishing. There are two versions of Daniel Webster and his record brook trout on Long Island. One has the site of its capture as the millpond of the old Wyandanche Club on the Nissequogue. The other version places the capture of the giant fish outside the graceful colonial church at Brookhaven, where Webster and his friends often fished at the Suffolk Club.

Brookhaven is still a quiet village among the beach-grass dunes and sheltered harbors of the South Shore. Its snug colonial saltboxes and elm-shaded streets have a special character, dominated by the slender bell tower of its Presbyterian church, built by local shipwrights in 1745. Such a patina of time is often enough to give a church some measure of fame, but this church is also part of the Webster legend. One hundred forty years ago its congregation apparently witnessed his legendary exploit with with the giant brook trout. Evidence supporting the story is relatively meagre: it consists of a carved cherrywood facsimile of the fish, obscure records and diaries, the brass plate of the Suffolk Club in one of the church pews, and the famous Currier & Ives lithograph of Webster catching the trout—a colorful lithograph that ultimately became part of the Congressional Record in 1854.

Webster himself is part of American folk legend, and his fame lies in several directions: orator, statesman, lawyer, congressman, and fly-fisherman. Webster was born at Franklin in the White Mountains of New Hampshire in 1782 and graduated from Dartmouth College. During both his boyhood and his college years Webster spent much time fishing the mountain brooks and brook-trout ponds of New Hampshire. He was elected to the Congress in 1813, and soon moved his residence to Boston. The legendary Dartmouth College case first gave him great fame as an attorney in 1819, and his defense of the United States Treasury in McCullough vs. Maryland cemented his reputation in the circles of power. His growing fame soon brought him into contact with men like Martin Van Buren, who would become president of the United States in 1837; Philip Hone, the mayor of the city of New York; and John Stevens, pioneer developer of steamboats, boilers, and locomotives. These men were all dedicated fly-fishers, and they subsequently invited Daniel Webster to join their Suffolk Fishing Club on Long Island.

Webster became a senator from Massachusetts in 1827, having established law offices in both Boston and New York. History tells us that he loved the brook-trout rivers found on eastern Long Island, and that his circle of fishing friends spent many weekends in the Fireplace Tavern operated by Sam Carman. It was a hard-fishing crew, fond of free-flowing rum and conversation that regularly gathered in front of his hearth, although each Sunday morning found them across the road in the Presbyterian church, nursing tehir headaches in the pew reserved for the Suffolk Club.

It was a bright spring morning in 1823 when Philip Hone first discovered the huge brook trout in the little river below Carman’s Tavern. Hone quickly found Webster and both men tried their luck for several hours without interesting the fish. Webster became obsessed with the huge brook trout, but it was four years later before he saw it again. Webster and Hone had left on the last Friday stagecoach from Booklyn, and arrived at the Fireplace Tavern long after dark. They found the dining room alive with stories of the giant fish. Downstream from the tavern Sam Carman also operated a general store and grist mill and that afternoon his employees had been working on its water wheel. When the work ù dismantling the big cypress-framed wheel ù had started, the huge brook trout had darted out from the millrace into the weedy channel upstream.

Webster and Hone fished the millpond through the following day without locating the big trout again. Saturday night found them commiserating their poor luck in Jamaican rum with liberal tankards of Carman’s of Carman’s hard cider for variety, and both men were ultimately carried to bed by Carman’s black servants. It proved a difficult and restless night. The following Sunday morning both men were faithfully seated in the pew across the road, perhaps groaning inwardly that the Presbyterian sense of austerity forbade such ornamental amenities as as stained-glass windows that might reduce the glare and mollify their headaches. Carman accompanied them to services that morning, but left instructions that his servant Lige should stand watch at the millpond for the giant trout. It was a beautiful spring morning and every man in the church stared longingly at the little river, with its pale willows and shadbush blooming and the ruby-colored buds of the swamp maples in the bend above the grist mill.

Parson Jedediah King was also a fly-fisherman but his long-winded sermons typically lasted all morning, and that morning was no King droned endlessly about temptation, the eternal faults of mankind, wickedness, hellfire and and brimstone, gluttony,, carnality ù and fixing his fierce blue-gray eyes on the Suffolk Club pew, debated the evils of cider and Jamaican rum. The sermon lasted an eternity itself. Shall we gather at the river, the congregation finally chorused, , the beautiful, beautiful river? The hymn finally ended, but the service still had thirty-odd minutes left.

There was a soft scraping at the churchyard door just as the congregation was settling for a second harangue from Parson King. Carman knew instantly what it was, and turned to see his servant Lige tiptoeing along the side aisle. Lige had located the big brook trout in the millpond, and only his orders to report sighting the fish could have forced Lige to interrupt Parson King and his morning services.

Lige slipped into the pew, and whispered to his employer briefly. Senator, Carman whispered to Webster, Lige has seen the big trout, it’s lying in the throat of the millrace, and it’s rising!

There is no subterfuge for leaving the front pew inconspicuously in the middle of a church service. Webster and Hone looked at each other briefly, averted their eyes and stook awkwardly, and quietly filed out of the church. The minister stopped and the congregation watched the four men leave. Every eye in the church watched them slip out the panelled door, quietly closing its polished-brass latch, and and everyone in the pews knew about the big fish.

Some of the men soon followed, nodding shamefacedly toward the pulpit and their wives, and soon only the pious women and children were left. Finally the minister himself succumbed, giving a hasty benediction as he moved down the aisle, and the remaining congregation followed. It gathered by the river to watch, as Lige rowed Senator Webster and Mayor Hone into position above the millrace where the fish was lying.

Webster caught a small brookie, and the millpond congregation groaned, thinking the big trout had had been frightened.

Thirty minutes passed and most of the of the congregation began walking home, when Webster made a long cast toward the grist mill and the fish was hooked.

Like all brook trout, this fish fought stubbornly under the trailing weeds and along the masonry foundations of the mill, and finally Webster forced it into the open, gravel-bottomed channel in the elodea and pickerel-weed.

The struggle lasted almost as long as the church service and sermon, with cheers and groans from the congregation, and finally the huge trout came grudgingly toward the skiff. It was almost black from living in the dark masonwork shadows under the mill wheel, its mottled gill covers and white-edged orange fins moving weakly. The faithful Lige reached expertly with the long-handled boat net. His words when he slipped the trout into its meshes are are included on the Currier & Ives print that recorded the event, and were later placed in the Congressional Record. We hab you now, sar! Lige laughed.

The congregation stood cheering along the millpond, and Parson King threw his prayer book into the air. Sam Carman and Lige wrestled the fish ashore, and carried it to the general store. Legend holds that the fish weighed as much as the current world record of fourteen pounds eight ounces, but it seems unlikely at best. Carman and Hone traced its outlined on linen, and their tracing was later transferred to a cherrywood plank. The carpenter made another wooden facsimile of the fish, enlarging it a third to give it a proportion equal to its lofty place on the weathervane of the church steeple . . .

[Conclusion not yet copied.]

_____________________________

p. 1626

The cast of characters has probably been embellished too, and everyone knows that our Republic would collapse tomorrow if men who disliked each other totally refused each other’s company.

The old Wyandanche Club on the Nissequogue had some Webster memorabilia in its collection, and the principal artifact of his triump still exists at the Bellport Historical Society. It is the cherrywood weathervane carved for the Presbyterian Church to commemorate Webster’s fish, bearing its honest scars of lightning. Such artifacts would not exist if the story were totally a myth. pointless challenges in recent months too.

The content or format of this subpage last updated: 09/28/2012 15:07:49

The first chapter of Nick Kara’s 1997 book, Brook Trout, brings the telling of the Webster “trout” story to modern times. In the annotated version below, Dr. Richard A. Thomas extensively footnotes Kara’s work, providing insights into some of the characters and places of the story, and highlights conflicts with historical facts which tend to question the authenticity of some of the details which have crept into the tale since the 1800s.