Maurice Wertheim

See also Leslie A. Davis, Letter from Harput, 1914 for another view of the Ottoman Empire of this period

Maurice Wertheim Involvement in Palestine, 1914

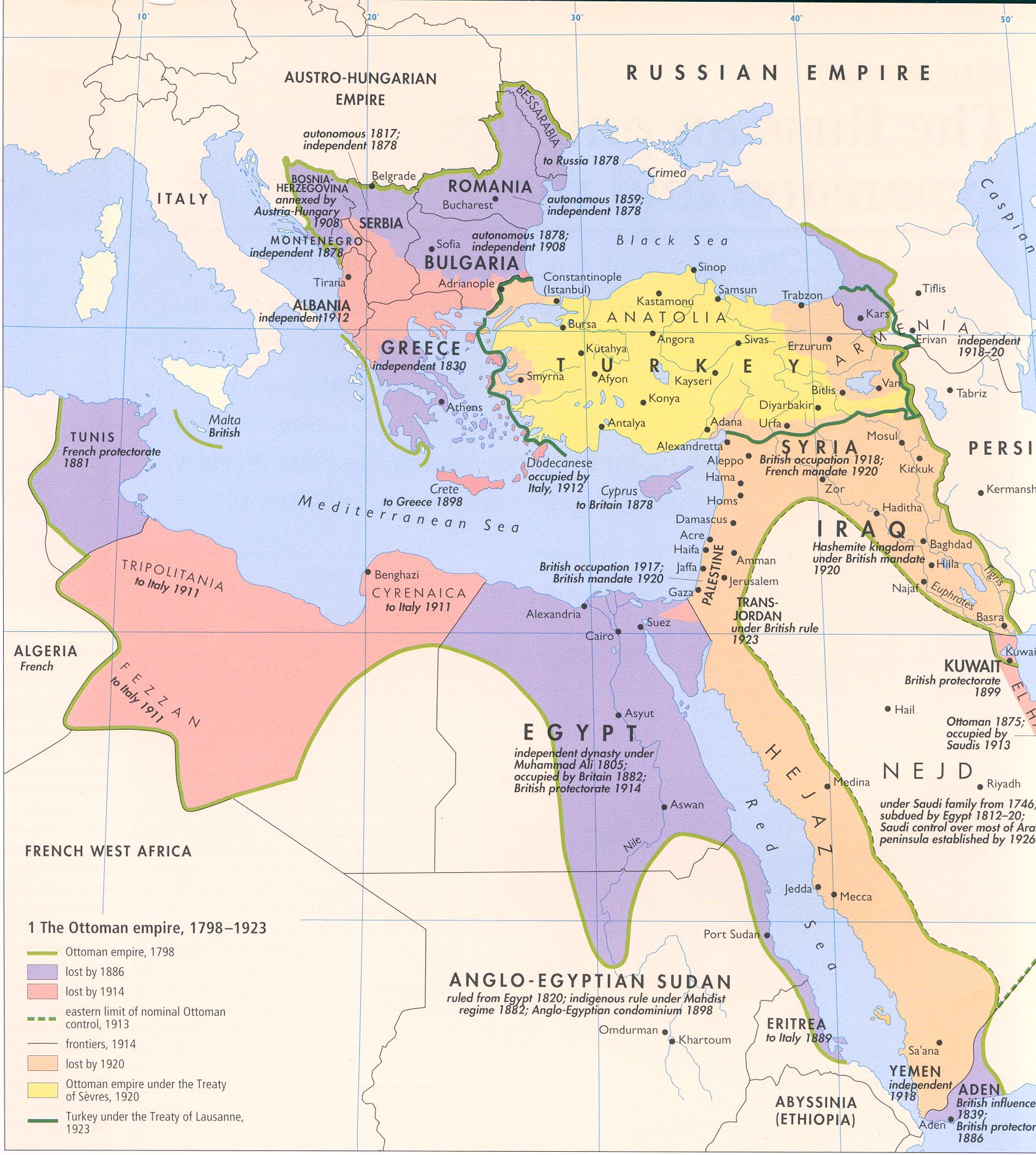

Turkey (the Ottoman Empire) joined the Central Powers to form the Triple Alliance with the signing of the August 1914 Turco-German Alliance. Turkey formally entered World War I on 28 October 1914, with the bombing of Russian Black Sea ports. The Triple Entente, or Allied Powers, declared war on the Ottoman Empire on 4 November 1914. The United States did not official declare war until 6 April 1917, hoping to remain neutral.

The Ottoman Empire included Palestine. Prior to WW I, the Zionist movement had been largely following a strategy of building a Jewish national homeland in Palestine through small-scale immigration and developing worldwide support organizations.

Henry Morgenthau, Maurice Wertheim’s father-in-law, was U.S. ambassador to Turkey at this time. The Turks had a history of persecution and out-right genocide of minorities within their Empire who were neither Turks or Muslims.

The following is an excerpt from a book by Henry Morgenthau III, Mostly Morgenthaus: A Family History (chapter 14, page 152-160), which includes a description of Maurice Wertheim’s involvement during this period.

[Henry] MORGENTHAU’S TWO-YEAR-OLD GRANDDAUGHTER Barbara Wertheim (later Tuchman), her parents, and two sisters were on board the Sicilia, a small Italian passenger steamer, in the Aegean Sea on their way to the American embassy in Constantinople for the family’s summer vacation [August 1914]. The historic events that took place at sea and after they reached port “became a big family legend,” Tuchman recalled. “I’ve told it many times, but I didn’t remember it personally.” Almost fifty years later, in The Guns of August, she described the scene without reference to its autobiographical connection, stating that “the daughter, son-in-law and three grandchildren [herself included] of the American Ambassador, Mr. Henry Morgenthau … brought an exciting tale of the boom of guns, puffs of white smoke, and the twisting and maneuvering of faraway ships.” Indeed, the Wertheims had witnessed the exchange of fire between the British light cruiser Gloucester and the two elusive German warships the Goeben and the Breslau.

When Tuchman decided to “do a book about 1914 as a critical moment in modern history, really the start of the twentieth century,” she had at first thought of simply writing about the escapades of the Goeben, but then decided that she needed a “broader canvas; certainly the family stories about the episode made the whole thing a lot more alive for me.”

Although Tuchman had no recollection of the historic skirmish at sea, she retained “a memory of the visit to Constantinople, that seems almost impossible because I was only two. And yet I have a memory and I tested it a few years ago [1976] when I went to Turkey.” She recalled a “white marble” building and “tall dark trees.” In Istanbul, what had been the embassy in 1914 had later become the consulate. With great difficulty she managed to be driven there. “I just had a chance to look in and sure enough it was white marble and there were tall, dark graveyard trees.” It was an impression that “must have been somehow stuck in my mind.”

Stephen Wise wrote Morgenthau on August 13, “I hope with all my heart that the Wertheims big and little have reached you in safety and that you will all be comfortably housed throughout the crisis.” He concluded, “The President is doing magnificently.”

War had been fatalistically anticipated, like some dreaded natural disaster. Although almost no one believed it could be prevented, some were already calculating its effects and planning for the aftermath. As the contending parties raced toward collision, all claimed to have God on their side.

From his vantage point in Constantinople Ambassador Morgenthau saw the war fulfilling his darkest presentiments about German militarism. Throughout his life, he had staunchly maintained that the antidemocratic, bellicose German spirit seriously threatened world peace. Though some German Jewish families maintained links of blood and commerce with the alte heimat, the Morgenthaus had permanently severed all such ties as soon as they arrived in America.

Public opinion in the United States was mixed. As a Jew with substantial German connections, Jacob Schiff was adamantly neutral. His continuing bond with the Germans and a long-standing hatred of their enemy, czarist Russia, for its brutal treatment of Jews, seemed in harmony with his Americanism. Wise was also propeace at first and opposed Wilson’s accelerated commitment to military preparedness.

Morgenthau began to observe the German warlord mentality, epitomized by Ambassador Wangenheim [German Ambassador to Turkey], Morgenthau’s apprehension grew as he witnessed Wangenheim’s blatant disregard for international agreements and manipulation of corrupt Turkish officials. But, as usual, prophetic vision was heeded too late. Morgenthau could see Enver steering Turkey into the German camp, while Talaat remained skeptical about it. Djemal, the least consequential member of the triumvirate, preferred friendship with the Allied powers. Single-minded and ruthlessly determined, Enver maneuvered his compatriots into making irreversible decisions binding Turkey to Germany, overlooking the risks of being swallowed up in the process.

Ambassador Morgenthau could see that the Germans intended to make Turkey not so much an ally as a vassal state under the skilled direction of Baron von Wangenheim, a complicated and explosive man, who dominated “not so much by brute strength as by a mixture of force and amiability.”

Wangenheim held to the Prussian policy of keeping “our governing classes pure, unmixed of blood,” but nevertheless went out of his way to cultivate the American Jewish ambassador and his family, whom under any other circumstances he would have found socially unacceptable. Morgenthau never allowed himself to be taken in by the Kaiser’s personal representative, fundamentally ruthless, shameless and cruel,” but was admittedly “affected by the force of his personality.”

Joining Wangenheim to help rebuild Turkey for German purposes, the extraordinarily talented General Liman von Sanders had come to Constantinople in December 1913 specifically to reorganize the Turkish army. His arrival attracted little notice. The Sublime Porte was accustomed to receiving German army and British naval missions. Like Baron von Wangenheim, General von Sanders found it prudent to ingratiate himself with Morgenthau. “I think Liman is one of the nicest men that I have ever met, and I expect to make quite a friend of him,” Morgenthau wrote his family in New York. “He told me that the Emperor talked with him for two hours the day he asked him to accept this post, and for three quarters of an hour when he said goodbye to him …. He is a widower and has two daughters. I expect Ruth will have them as her friends.” Things did not work out that way.

The ragtag army that the Turks handed over to General von Sanders was completely demoralized. The officers, with salaries three and a half years in arrears, could not afford uniforms. When Morgenthau invited some of them to an embassy reception, they begged to be allowed to wear evening dress; when the grand vizier vetoed this suggestion, they were obliged to absent themselves. The enlisted men could not even be drilled because they had no shoes.

Army conditions exemplified the general state of destitution in the empire. Whereas Enver was enthusiastic about the prospects for Prussification, Talaat believed, as he told Morgenthau, “that he was using Germany, though Germany thought it was using him.” However, with the infusion of German funds and expertise, the military transformation was phenomenal. One Sunday afternoon in January 1914, Morgenthau and his son were given a two-and-a-half-hour tour in the new French Panhard automobile owned by the heir apparent to the sultan. “As you ride through the country,” the ambassador noted, “you really think that you are passing through an encampment. We met at least six different regiments of soldiers drilling, exercising and maneuvering.”

With all resources concentrated on mobilization, conditions for the general population grew ever more desperate. Out of 4 million adult males, more than 1.5 million were eventually conscripted. Soldiers were paid about 25 cents a month, and their families received an allowance of $1.20 a month. Evasion of military service was a crime punishable by death. One could obtain exemption by payment of about $190, a sum almost no one could afford.

Similarly, the requisitioning of supplies “amounted to wholesale looting of the civilian population.” Most merchants were not Muslims, and Morgenthau thought the Turks seemed to find “a religious joy in pillaging the infidel establishments.” Even more devastating was the requisitioning of livestock regardless of civilian needs. Thousands of people were left enfeebled and starving. Morgenthau later estimated that the empire had “lost a quarter of its Turkish population since the war started.”

Enver, as minister of war, seemed without compassion for his people and was impressed only by “his success in raising a large army with practically no money.” But his true strength lay in German hands. A rapid succession of dramatic events locked Turkey’s destiny with Germany’s, and it became clear that Turkey had forfeited its right to any independent choice of options.

Perhaps the outcome was inevitable. At the outbreak of war, on August 2, Turkey and Germany had signed a secret agreement to ward off aggression from Russia, for centuries the primary threat to Turkish security. Since England and France were allied with Russia, the Turks were obliged, however reluctant some might have been, to join the German-Austrian camp.

A week after the Wertheims observed the Goeben and the Breslau, the ships arrived at the straits of the Dardanelles. Having escaped the vastly superior British naval forces, the Germans had no choice but to enter neutral Turkish waters. To the British, such a violation of international law was unthinkable. But when the Germans demanded to have their warships take shelter in Turkish waters, Enver, with no time to consult his peers, single-handedly acceded. In what turned out to be an instant of momentous historic importance, Enver had resorted to a thinly disguised ploy permitting the Germans to “sell” their men-of-war to the Turks. On the rechristened Jawus and Midilli, the German officers donned fezzes and steamed through the straits to safe harbor. The kaiser now virtually held the Turkish government hostage.

Boisterous German arrogance knew no bounds. Ambassador Morgenthau made note of a day when “the Goeben sailed up the Bosphorous, halted in front of the Russian Embassy . The officers and men lined up on the deck … all solemnly removed their Turkish fezzes and put on German caps.” Thereupon, the sailors, accompanied by a military band, serenaded the Russians with “‘Deutschland Uber Alles,’ ‘Watch on the Rhine’ and other German songs” before once again donning their fezzes and steaming back to their station.

In the first weeks of the war, the Turks, maintaining their officially neutral position, deluded no one but themselves. Wangenheim boasted to Morgenthau that the Dardanelles could be closed to shipping within half an hour. On September 27, on the flimsiest of pretexts, the German general in charge at the mouth of the straits did just that. “Down went the mines and the nets. The lights in the lighthouses were extinguished.” When Sir Louis Mallet [British Ambassador to Turkey] and Morgenthau rushed to lodge their protests with the grand vizier, they were shocked to learn that his government had received no advance warning. In one stroke the Germans had severed Russia’s only warm-water lifeline and isolated the country from its allies.

It took only one more stroke to maneuver the Turks into war. A few days after the straits were closed, three Turkish gunboats entered the harbor of Odessa, with German officers in command. It was the religious holiday of Baivam, and there were few Turks on duty. Without provocation, the Germans attacked Russian and French warships and shelled the town. Still it was only in late October that the Russians, faced with no alternative, declared war on Turkey.

The U. S. ambassador suddenly found himself confronted with challenges of far greater magnitude than he had anticipated. As the Allied envoys left, they put their embassies and their nationals in his custody. At intervals he became responsible for safeguarding a total of eight national groups. The situation became particularly difficult when the Turks, furious with the British and French as their military forces tried to storm their way back through the Dardanelles, announced that they were sending the two or three thousand Allied citizens in Constantinople to Gallipoli “as targets for the English and French ships.” At the time it seemed like “an ingenious German scheme to discourage the English blockading fleet, not unlike the stationing of Belgian men and women in front of the advancing German armies in Belgium.” As the last mediator on the scene, Morgenthau, who had remained on good personal terms with Enver, went to bargain with him. Enver “finally consented to send only fifty and the youngest men be selected.” Soon afterward Morgenthau’s successful haggling for these hostages “brought the party back without loss.”

The ambassador’s greatest challenge came not in protecting enemy aliens, however, but in trying to stop minority persecution within the empire. As in earlier times of stress, the Turkish government resorted to scapegoating those who were neither Turkish nor Muslim. The only possibility for benign intervention seemed to be the neutral Americans.

Ambassador Morgenthau kept the State Department informed with cables describing Near East developments and his analysis of them. He received little feedback and less guidance except occasional cautionary admonitions, which he chose to interpret as a license to exercise his best judgment, consistent with American ideals. But while the voices in official Washington remained muted, the voices of private constituencies – especially Christian missionaries and Jewish organizations – came through loud and clear. They were all Morgenthau needed to be prompted to vigorous action.

Early in 1915 Turkish officials began to interfere with communications from the interior. Morgenthau meanwhile was receiving alarming news about Palestine from Grand Rabbi Nahoum in Constantinople and the organized Jewish community in New York. Furthermore, the Turks, while planning their “final solution” for the Armenians, seemed to have a similar fate in mind for the Jews and other minorities under their control.

When the war began, nearly everyone imagined it would end quickly, probably with a settlement negotiated by the United States. This expectation hardly mitigated fears among Ottoman Christians and Jews that once they were cut off from the benevolent concern of the Europeans the Turks would destroy them. For the Jewish community in Palestine, heavily dependent on outside aid, the prospect of economic strangulation was especially frightening. No one was more disturbed than Ambassador Morgenthau, who had gained a thorough understanding of the precarious situation during his visit to the Holy Land.

On August 28, acting quickly and decisively, Morgenthau cabled Jacob Schiff in New York for help through official State Department channels:

PALESTINE JEWS FACING TERRIBLE CRISIS. BELLIGERENT COUNTRIES STOPPING THEIR ASSISTANCE. SERIOUS DESTRUCTION THREATENS THRIVING COLONIES. FIFTY THOUSAND DOLLARS NEEDED BY RESPONSIBLE COMMITTEE.

Schiff passed the word to Louis Marshall, president of the American Jewish Committee, “suggesting” a meeting of the committee “at once.”

The committee convened on August 30. Early on September 2, Schiff, on his own initiative, cabled Morgenthau “accepting your suggestion, and authorizing you to go ahead in carrying it out.” Later that same day he notified Morgenthau: “We had a meeting of the executive committee of the American Jewish Committee, which approved of what I had done, contributing from their own funds $25,000, while I undertook to add $12,500 and it is expected that the American Federation of Zionists will furnish the remaining $12,500, but be that as it may, the entire $50,000 will be at your disposal as soon as we hear from you to whom to remit.”

Ambassador Morgenthau arranged with the Standard Oil Company to have the initial gold payment from the United States released through Standard’s representative in Constantinople. From there, it was transported aboard a battle cruiser, the USS North Carolina} with his son-in-law Maurice Wertheim serving as his personal emissary.

Delivering the American gold and seeing to its equitable distribution among the Palestinian Jews’ was a difficult, highly visible assignment, which inspired mixed reviews from the local Jewish press. The Palestine Jews were acrimonious and fragmented, split between the Zionist agricultural colonies and the religious groups concentrated in Jerusalem. A supposedly representative committee led by Dr. Ruppin, head of the Zionist office in Jaffa, was authorized by donors in New York to set up a loan institute. At Morgenthau’s suggestion, Aaron Aaronsohn, managing director of the. Jewish Agricultural Experiment Station at Haifa, was added to this. body. All of these men were ardent – though not necessarily political Zionists, but religious Jews, the conspicuous minority in representation, were vocal in their claims.

The American battle cruiser North Carolina entered Jaffa harbor on Thursday, September 24, 1914, like a miraculous apparition. Dr. Ruppin, in the company of the new American consul, the Reverend Otis A. Glazebrook, welcomed Mr. Wertheim. “There was a large crowd on the land-station to witness the scene,” Ruppin reported to Morgenthau. “The fact that the son-in-law of the American Ambassador on board an American cruiser has brought subsidies from the United States for the Jews of this country has deeply impressed the Palestinian population and will no doubt have a wholesome effect on people’s attitude … and the people have become aware of the fact that, although the Jewish community here is not yet strong as far as the number of its members are concerned, it receives strong support from our co-religionists abroad.”

The gold itself, which Wertheim carried in a suitcase, caused great excitement. According to Ruppin, it was immediately deposited in the Anglo Palestine Company Building. Barbara. Tuchman recalled her father telling the story of locking himself in a room with the gold and refusing to come out until the loudly disputing parties reached an agreement.

The same day, Dr. Ruppin wrote Morgenthau that he had given Wertheim “the same tour which I have made with you of the Jewish colonies in the Jaffa-Tel Aviv area.” Two days later, Saturday, Wertheim received the heads of several institutions in Jerusalem “and requested them to inform other Jerusalemites that the money was not intended for individuals who lived on charity, but to aId 111 its hour of need the yishuv which supported itself by productive work.” Concerned with matters of life and death, these meetings appear to have been exempt from Sabbath restrictions. “On Sunday morning Mr. Wertheim visited the Haham Bashl [the title accorded by Ottoman rulers to the chief rabbis, and in Palestine to the chief Sephardic rabbi] and at two that afternoon the Haham Bashl accompanied by several members of the committee, returned the call.” The following day the distribution committee went to Haifa to meet with Aaronsohn and make the final arrangements for apportioning the funds. Everything had been “done with lightning speed, in the American way.”

Before the end of 1914 the Wertheim clan were all back home in New York. Wise wrote Morgenthau that he thought Wertheim’s “visit to Palestine and what he did there will make a permanent difference throughout his life. We had the delight of seeing Alma as well as Maurice and those three lovely little girls.”

Morgenthau had served as the catalyst in a feat of international social networking that momentarily saved the frail Jewish community from extinction. It was a historic benchmark but not a turning point in a battle during which mortal threats continued to mount.