Maurice Wertheim

Maurice Wertheim — Degas to Matisse

Our interest in Maurice Wertheim largely derives from his donation, along with his wife, of his South Haven hunting lodge estate to the Federal government to become the core of the Wertheim National Wildlife Refuge. There are few now living in the hamlets of Brookhaven and South Haven who remember Wertheim, he having died in 1950. A few more, perhaps, remember his wife, Cecile, who was a not infrequent visitor to the estate until her death in 1974. Those who remember the Wertheims are mostly Degas to Matisse Book Coverchildren of those who worked on the estate. Many remember roaming the estate as youth, relatively unimpeded, especially when the Wertheims were not in residence.

It is interesting to note that this hunting lodge estate, which they called Stealaway—situated on some 1,800 acres when deeded to the Federal government—is infrequently mentioned in family reminisces and biographies. The impressions of those local residents who still remember their tenancy, was that it was a very private retreat for Maurice and his wife, and a few close friends with similar interests (the Wertheims also had a large mostly rural estate in Cos Cob, Connecticut; a fishing lodge on the Gaspé Peninsula, Quebec, Canada; and a home in Cuba). The estate lodge on the banks of the Carman’s River, was very modest, not much more than a shack in the woods. ![]() Click for Footnote The farmland that once occupied most of the land was allowed to return to its natural state, and the river and bay marshes were left undisturbed. Little was known locally of the man, Maurice Wertheim.

Click for Footnote The farmland that once occupied most of the land was allowed to return to its natural state, and the river and bay marshes were left undisturbed. Little was known locally of the man, Maurice Wertheim.

As we have researched Maurice Wertheim as part of our hamlets history project, we have come to see that Wertheim was very much what we might call a “renaissance man,” although I have never seen that label attached to him. His interests included not only banking, but philanthropy, politics, social service, theater and art, the environment, and fishing. As he himself wrote: “Sometimes, in a light moment, I say about myself that my chief interests in life are banking, the theatre and fishing, but that their importance to me is in the inverse of the order named.” [Maurice Wertheim—1931 Report to the Harvard Class of 1906.] His progeny also distinguish themselves, including well known authors and environmentalists.

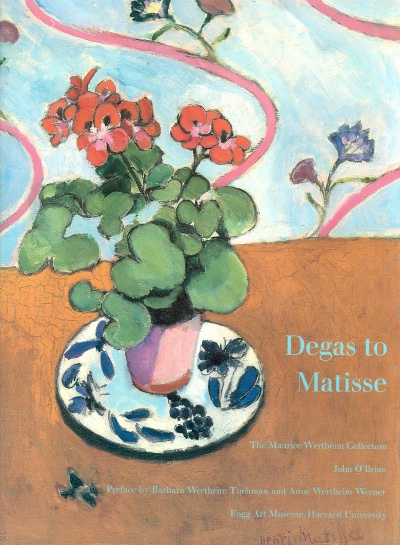

The following account, written by two of his daughters, Barbara Wertheim Tuchman and Anne Wertheim Werner (he had three daughters), provides insight into their father. It was written as the Preface to Degas to Matisse: The Maurice Wertheim Collection, by John O’Brien of the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 1988.

Father assembled his superlative collection of Impressionist paintings and sculpture in the same style as he did most of his various activities—with vigorous enthusiasm and determination to achieve the best. From his mid-forties until his death at sixty-four, the collection was a central source of pleasure and enormous satisfaction to him.

The engine that drove him was the desire to play an active role in a variety of endeavors-cultural and intellectual, philanthropic and sporting—aside from the business of finance that was the substance of his career. The distinctive quality of his bent was its diversity, but MW, as friends and family called him, almost always wanted to be in a position to give the activity form and direction, to innovate and create. He was not by nature a subordinate, nor content with the second-rate. He searched for excellence and for undertakings that were first class of their kind.

Impressionism, in fact art in general, was not a youthful interest. MW began finding his own way early, leaving his father’s business to join the investment banking firm of Hallgarten & Company. He was made a partner before he was thirty and within seven years took the risky step of leaving Hallgarten, to the concern of family and friends, to found his own firm of Wertheim & Company, which he headed for the rest of his life.

Father was a passionate fisherman, so much so that when his first grandchild was born, he announced that he had been awake all night figuring out how old he would be when the baby boy could take his first salmon, in order that he could teach him the fine points of the sport. Another passion was chess, a skill much practiced at the Manhattan Chess Club, and with chess-by-correspondence, which required agonizing waits for the next move to arrive by postcard. He did more than simply play; becoming president of the Club, he organized a chess team to compete with the USSR team and led it in person to Moscow, a daring and successful adventure.

Participating in Jewish affairs, MW was a trustee of the preeminent Mount Sinai Hospital and of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies, and at a crucial time—1941-1942—president of the American Jewish Committee, the body of entrenched conservatives who possessed considerable prestige and power. Against the antagonism of many old friends and associates, MW prodded the AJC out of its rigid hostility to Zionism. He was able to turn it around to support the movement for statehood that was an answer to Hitler, probably the most difficult and historically the most important action of his career.

He had already undertaken two cultural exploits of some note. As small girls, we went with him to Broadway opening nights of productions presented by the Theatre Guild, of which he was a founder and director, along with five self-assured, strong-minded, and temperamental individuals. No one short of Julius Caesar could have dominated these personalities—actress Helen Westley, director Philip Moeller, stage designer Lee Simonson, father’s fellow businessman Lawrence Langner, and Teresa Helburn, who eventually took over direction of the Guild. They met by turn in each other’s homes, and we can well remember the raised voices from the dining room when they came to our house, the shrieks of argument and laughter, and the often stormy departures as the choice of plays and performers for the new season was being decided. Out of all that discord and violent brouhaha—as it seemed to us eavesdropping children, for there was something quite exciting about adults in such unbuttoned behavior-—they produced an outstanding record of the best theatre with the best plays and performances in the land.

There was excitement of a different sort about MW’s purchase of The Nation magazine. Through association with Freda Kirchwey, Mother’s friend and Nation editor, Father became concerned at the magazine’s drooping fortune during the Depression, and he bought it to enable it to continue with Freda in charge. He took on this new and to him unfamiliar activity with an ability, unusual for a man of his type, to seek out someone who could give him sound and reliable advice and, what is more, to accept it. In this instance the person was Alvin Johnson, president of the New School, for whom, as a kind of universal teacher, MW had great respect, and he was glad of his guidance through the thorny business of publishing a journal of opinion.

In his accustomed active fashion, MW relished our Connecticut home, “here we spent summers and winter weekends. He fished in the lake, supervised the farming, set up a model dairy and a chicken coop, and one year he imported several flamingos and black swans, having glimpsed their like in a European castle pond. He rode horseback with his wife and three daughters, setting a breakneck pace.

When his pace was slowed by some fundamental personal disruptions, Father was advised to find a new interest. And he did.

He immersed himself in the art world, starting almost from zero. With the same instinct for finding the right advisor, he sought out Alfred M. Frankfurter, editor of Art News, an expert in the subject of art. Frankfurter and others took the zealous student on a round of galleries and museums at home and abroad. Bookcases were rearranged to accommodate tall, heavy art books, talk was of auctions, dealers, private showings. Soon Father focused his enthusiasm on the French Impressionists … and the collection was underway.

Huge, crated canvases arrived at our terraced apartment on East 70th Street in New York. There were intense conferences about framing, hanging, lighting, and about next acquisitions. Friends were impressed with each new purchase. MW’s butler, Charles, a gentleman’s gentleman right out of “Upstairs, Downstairs,” speedily learned a store of anecdotes about the works to tell visitors whom he showed through the collection.

The three of us failed to provide much in the way of applause. Jo, the eldest, who died some years ago, was engrossed in starting married life; Barbara, already a journalist, was abroad and hardly noticed MW’s new undertaking; Nan, with a teenager’s untutored eye, was not impressed by breakfasting with Renoir’s nude bather. Later, Father and youngest daughter had a mighty battle when she refused to get married under Picasso’s Blue Period painting of a syphilitic mother and infant, which was hung over the fireplace, and he refused to take it down. The family lawyer resolved the deadlock with a diplomatic compromise—a smilax curtain draped over the painting to be removed instantly after the ceremony.

Father’s new enthusiasm absorbed most of his nonbusiness time and dictated the way he lived. Most Saturdays he devoted to looking at art with his new wife, the former Cecile Seiberling, a knowledgeable art enthusiast in her own right. When the collection grew too large for the apartment, MW bought a capacious town house a few doors down the street, with high-ceilinged rooms to give the paintings needed space.

As his appreciation grew, MW determined upon acquisition of the Impressionists’ finest works. With his own decisive taste and Frankfurter’s guidance, the collection, always highly selective and never succumbing to the merely popular or well known, included original and exciting examples of each painter’s and sculptor’s art—van Gogh’s Three Pairs of Shoes, Lautrec’s The Black Countess, Degas’s Singer with a Glove—these and other works of equal quality give the Wertheim Collection its distinction.

MW had endless meetings and spent much thought on the ultimate disposition of his paintings and sculpture, bargaining hard with one museum or another for conditions that he thought appropriate. He was intent on keeping the collection together, believing it had more meaning as a group of works that complemented each other, and so turned a deaf ear to any institution that would have separated it or sold part of it, and just as firmly ignored all hints, suggestions, and outright pleas from members of his family who cherished fantasies of inheriting a favorite masterpiece. An ardent member of the Harvard Class of 1906, he was gratified to reach agreement with his alma mater as the collection’s ultimate home [the Fogg Museum], and surely, were he alive to do so, he would have enthusiastically written this preface himself.

Barbara Wertheim Tuchman

Anne Wertheim Werner