New York Times, 29 December 1966, p. 31

GARDNER REA, 72, CARTOONIST, DIES

His Sharp-Edged Drawings Appeared in New Yorker

Gardner Rea, the cartoonist, died yesterday in Brookhaven Memorial Hospital on Long Island after a after a long illness. He was 72 years old.

Mr. Rea, a resident of Brookhaven for four decades, had become almost a recluse in recent years. But he still drew the sharp-edged drawings that had been his style from the first issue of the New Yorker magazine, though not as frequently as in the past.

One of his lines that remains in the language went with a drawing of two street venders holding a sidewalk conference. “Does Gimbels tell Macy’s?” one of them is saying.

Another cartoon showed a disappointed member of the audience after Walt Disney replaced his animal characters in an ambitious musical film. His comment was, “What, no Mickey Mouse?

Mr. Rea in a photograph published in the mid-1940s.

Sold Cartoon at 15

Born in Ironton, Ohio, Mr. Rea came from an artistic family. He was planning to be a serious painter, but at the age of 15 he sold a gag cartoon to the old Life magazine and never recovered. That event is documented in his Who’s Who biography in the entry, “Freelance cartoonist (1907).

From East High School in Columbus he went on to Ohio State University, where he became one of the smallest Big Men On Campus: weighing only 90 pounds, he won his letter in tennis, edited the humor magazine and was active in other undergraduate publications.

He was particularly proud of winning the annual prize of the Serious Poetry Committee and the Humorous Poetry Committee — with the same poem.

After his graduation in 1914, Mr. Rea resumed his freelance career, this time in Manhattan, contributing verse, essays and drawing to the two leading humor magazines of the period, Life and Judge. In World War I he served as an enlisted man in the Chemical Warfare Service. In 1920, he married Dorothy Julia Calkins, an artist who had recently graduated from Pratt Institute. Shortly afterward they moved to the home they designed and built in Brookhaven.

Aided Colleagues

When Harold Ross was gathering talent to start a magazine called The New Yorker in 1925, Mr. Rea was one of the original contributors. An old college friend, James Thurber, was in Paris at the time, but joined the magazine the following year.

Rea’s contribution was considerably more than the drawings that appeared under his name. Some associates considered an equal talent was his short, sharp gags that formed the basis for cartoons by such noted colleagues as Charles Adams and the late Helen Hokinson. At one time he wrote about 40 gags a week, most of which he sold to editors.

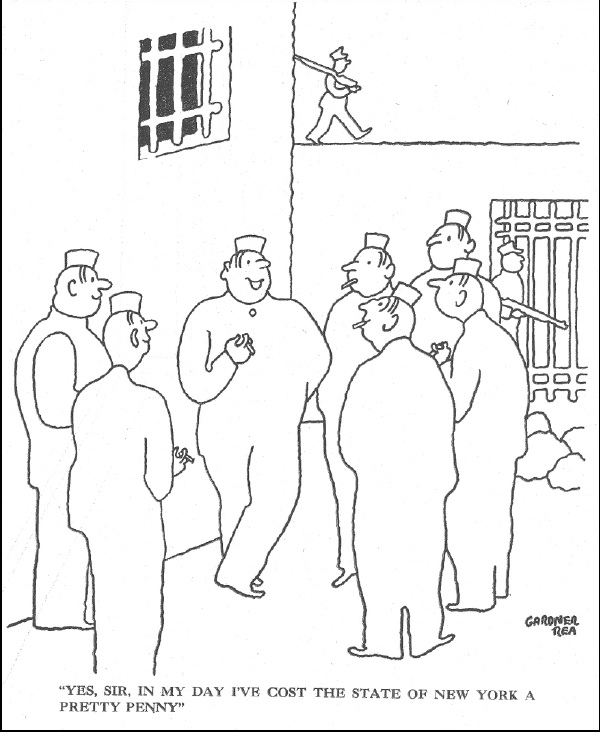

That somewhat serpentine line of his drawings, without detail, became his trademark, along with a trick of having in each picture a small shape, such as a necktie, inked in solid black. He explained the “wiggle” of his line with another gag—”Nobody will catch on when I get senile.”

But Mr. Rea distinguished between verbal humor and the art of drawing. He told an interviewer in 1946 that in common with most critics, he considered “that line is the highest, most difficult form of art, and so long long as the fundamental design is there, I can’t see that it makes the slightest difference, technically speaking, if the subject matter is humorous.”

No Front Door

His aloofness inspired Ogden Nash’s observation that “he lives in a diving bell at the bottom of Long Island Sound.” And he once told a guest that he visited New York only once a year, to see his editors. The only way for Mr. Rea to leave his house was by the back door, since he planned his house without a door facing the street. Similarly, he chatted genially with his visitor while facing a blank wall.

Many of his drawings were selected for humor anthologies. Two collections of his own works have been published: “The Gentleman Says It’s Pixies,” selected from his contributions to Collier’s magazine, issued in 1944, and “Gardner Rea’s Sideshow, which included cartoons that also appeared in The New Yorker and The Saturday Evening Post, in 1945.

The latter was dedicated “To my beloved family — despite whose untiring efforts, this modest opus finally saw the light of day.”

In his years of withdrawal, Mr. Rea read deeply in anthropology and psychology and developed a reading knowledge of 12 languages. He enjoyed chamber music and the clay tennis court in his backyard.

His wife died last summer. Surviving are to daughters, Mrs. John G. Dalrymple and Mrs. Roy E. Renwick, and five grandchildren.

A funeral service will be held tomorrow morning at 10 o’clock in St. James Episcopal Church in Brookhaven.